Institute of Neuro-Semantics Europe

Coaching and Neuro-Sience

Dr. Irena O’Brien is a Meta-Coach, Neurosemantic Trainer, and a cognitive neuroscientist. She has been studying psychology and neuroscience for over 20 years. After working as a chartered accountant for 15 years, she went back to university and obtained her PhD in Psychology from the Université du Quebec à Montréal. While there, she conducted brain imaging and electrophysiological studies and went on to do a postdoctoral fellowship at the Centre for Language, Mind and Brain at McGill University. Dr. Irena is passionate about neuroscience. She reads and writes about the latest research in neuroscience and psychology, which offer us practical tools and strategies that we can use with our clients and in our own daily lives. She is a testament to that, continuing to use what she learns from neuroscience in her own life and that of her family.

Which is why she founded The Neuroscience School, a neuroscience training and information programme for coaches and health and wellness professionals, where she un-complicates neuroscience and teaches practical evidence-based tools and strategies her students can use in their practice. One of her pet peeves is the misinformation about neuroscience that floods the media and her goal is to right that wrong. Dr. Irena is particularly interested in how our lifestyle choices impact brain structure and function, affecting mood and cognitive functioning. She is a firm believer that having a healthy brain and mind requires a healthy body.

For more information about Neuro-Science and Irena O’Brien please click on the link of the Neuro-Science School. http://neuroscienceschool.com/

How Accepting Negative Thoughts Contributes to Psychological Health

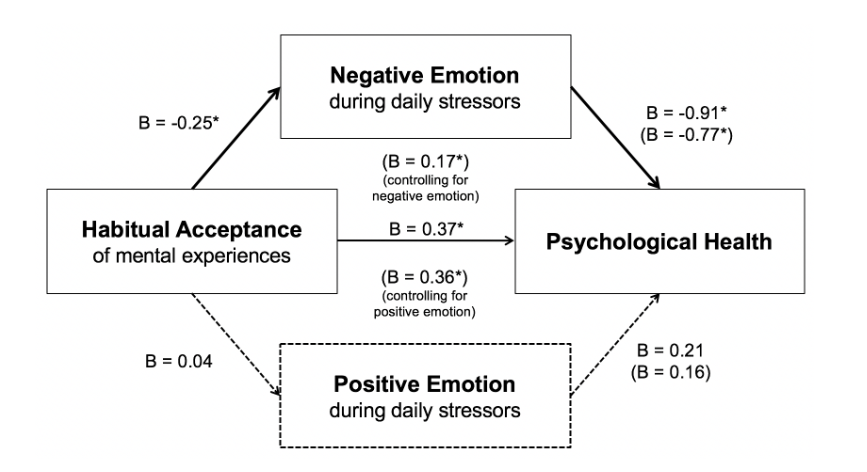

In a recent paper, three studies looked at how accepting negative thoughts could contribute to psychological health. The first two studies investigated the effects of acceptance over the short term. The third study examined these effects over a six month period. In this third study, participants were 222 community-dwelling adults who had experienced a stressful event within the 3 months preceding recruitment to the study. The sample consisted of a variety of ages, ethnicities, and SES (socio-economic status). At the start of the study, the participants reported the extent to which they habitually accepted their mental experiences using validated questionnaires. For the next fourteen days, the participants kept daily diaries of their emotional responses to daily stressors. Finally, six months after the diary assessment, they completed measures of psychological health as well as a measure of the stress they had experienced in the preceding six months, using validated questionnaires. The researchers found that participants who habitually accepted their mental experiences had better psychological health than those who did not (B = 0.37). And this relationship was negatively mediated by their negative emotions during daily stressors (B = -0.25). This means that those who habitually accepted their emotions and thoughts experienced fewer negative emotions which led to better psychological health (B = – 0.91). And this was irrespective of gender, ethnicity, or SES.

What Multi-Tasking Really Costs You

In our 21st century world of wanting to do more and more in less time, skilled multi-tasking has become the holy productivity grail. But, the research shows that multi-tasking, the attempt to do two or more tasks at the same time, is really just fast task-switching and the costs are heavy – people make more mistakes or perform their tasks more slowly.

Key Takeaway

Our brains are unable to keep two things in mind at the same time. That means the brain can’t multi-task. When we think we’re multi-tasking, we’re actually switching tasks quickly. When we try to multi-task, the cognitive resources available to both tasks is reduced, resulting in reduced productivity and increased errors. The cost in productivity may be as high as 40%.

The human attentional system has limits for what it can process.

Much of the research on multi-tasking has looked at driving while performing another task, such as texting, eating, or speaking to passengers in the vehicle, or with a friend over a cellphone. This research reveals that the human attentional system has limits for what it can process: driving performance is worse while engaged in other tasks; drivers make more mistakes, brake harder and later; they get into more accidents, veer into other lanes, and are less aware of their surroundings.

In one study that looked at brain activations during distracted driving, the participants drove in a simulator under varying difficulty levels. They also listened to an audio of general knowledge true or false questions (such as a triangle has four sides) and answered the questions by pressing buttons on the steering wheel. So the design of this study was similar to real driving conditions.

The researchers found that as the driving conditions became more difficult – turning left into oncoming traffic – the audio task shifted brain recruitment from the crucial parietal and visual cortices, which are responsible for spatial and visual processing, to the frontal areas, responsible for executive functions including attention, working memory and decision processes. Obviously, this is not a good thing. When we need our parietal and visual cortices the most, turning left into oncoming traffic, the frontal areas hijack some of our crucial spatial and visual brain power to accomplish the audio task.